Advanced Therapies Aimed to Treat Diseases of the Eye

Our mission: to restore vision to millions of patients with life-changing regenerative therapies

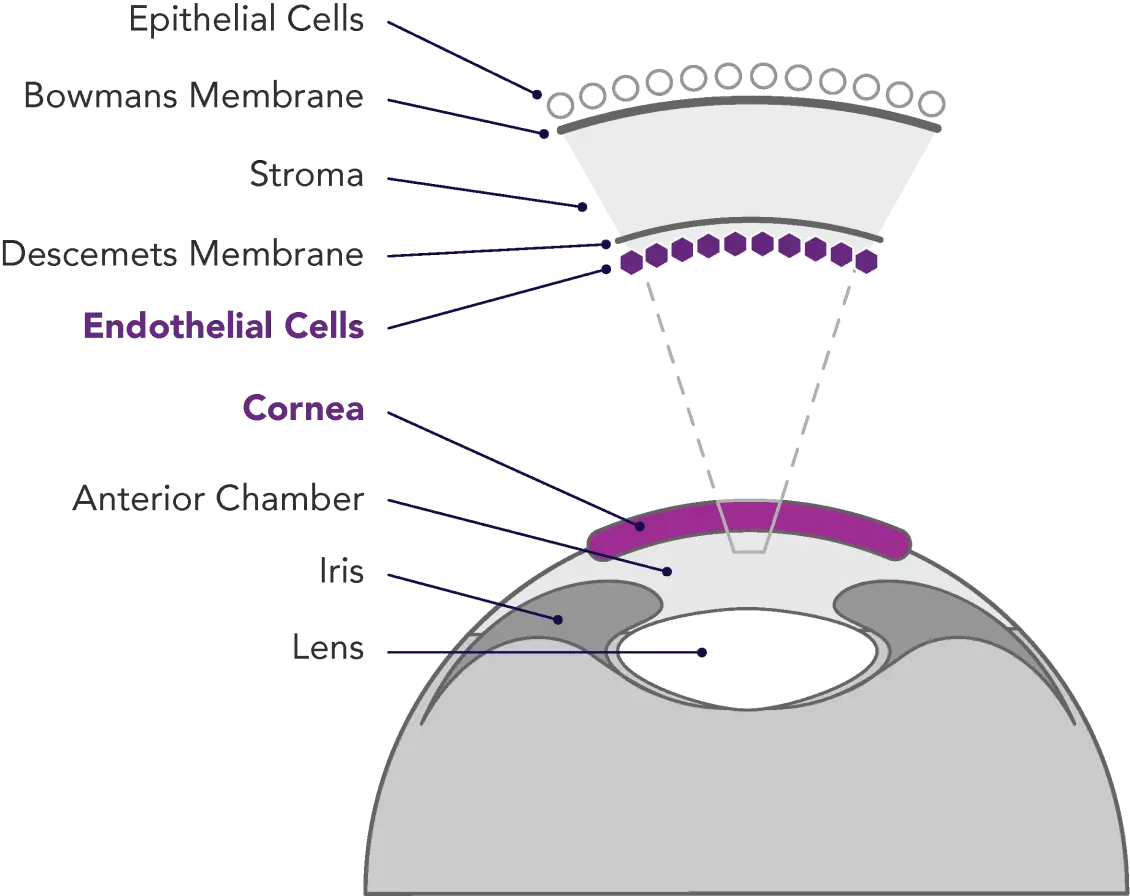

Corneal endothelial disease is a sight-threatening and debilitating condition affecting millions of people throughout the world. Composed of a single layer of cells located on the posterior surface of the cornea, the endothelium serves both barrier and pump functions. The integrity of the corneal endothelium is essential to the maintenance of corneal clarity and optimal vision.

The cells of the corneal endothelium are incapable of regenerating. Once these cells die – due to diseases such as Fuchs dystrophy, surgical trauma, and/or congenital dystrophies that lead to endothelial cell loss and vision degradation – they are gone forever. Symptoms of corneal endothelial disease may include blurring, glare, discomfort, and, in some cases, severe pain.

Although topical therapy can relieve symptoms of early-stage disease, the only disease-modifying treatments for more severe corneal endothelial dysfunction are full- or partial-thickness corneal transplantation, referred to as penetrating (PK) or endothelial (DSAEK, DMEK) keratoplasty, respectively.

Corneal endothelial disease progression

Simulating the patient’s perspective

- Patient with 20/20 vision

- Patient sees glares and halos at night

- Contrast and brightness diminish

- Vision becomes blurred and uneven

- Objects are opaque, difficult to distinguish

Treatment options

While these EK methods are effective, there is a sizable gap between the number of healthy donors available for transplant and the number of patients in need; according to one survey, there is only one healthy donor cornea available for every 70 diseased eyes globally.

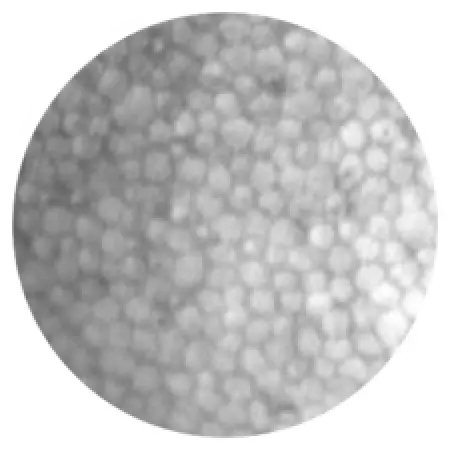

Healthy endothelial cells

Damaged endothelial cells

Reference

- Gain, P. et al, Global Survey of Corneal Transplantation and Eye Banking, JAMA Ophthalmology, 2016;134(2):167-173. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.4776